Q & A with Mark Whitehead

Mark Whitehead, PhD, is the chief of the Anatomy Division in UC San Diego's Department of Surgery. In this interview with Communications Director Lindsay Morgan, he discusses his research on neuroplasticity, and specifically how taste information is processed by the central nervous system; UC San Diego's dissection-based approach to anatomy education; and whether anatomy is being squeezed from the medical school curriculum?

Mark Whitehead, PhD, is the chief of the Anatomy Division in UC San Diego's Department of Surgery. In this interview with Communications Director Lindsay Morgan, he discusses his research on neuroplasticity, and specifically how taste information is processed by the central nervous system; UC San Diego's dissection-based approach to anatomy education; and whether anatomy is being squeezed from the medical school curriculum?

July 25, 2017 | Interview by Lindsay Morgan

You got your PhD in 1977 in the University of Rochester in Neuroscience.

I actually got my degree in Anatomy. Back then, most neuroscience training occurred in anatomy and physiology departments. I wanted to be an anatomist. And I wanted to do neuro-anatomical research.

Where did that interest come from?

My father died at an early age of an ultimately undiagnosed neurological problem. That got me interested in the brain. And I had a job in a hospital when I was in college, doing lab analysis of samples from patients, and I liked working in the lab. So, I carved out this interest in science and the brain.

In the 40 years since you got your PhD, in addition to teaching, you've been a PI on a number of research projects and have had continual NIH funding for 30 years—quite a feat. Your most recent work looks at how taste information is processed by the central nervous system.

I'm interested in neuroplasticity—how does the brain recover from injury? What's the nature of neural regeneration? Why are there limits on the degree to which the nervous system can repair itself after injury?

It turns out that the taste system is a good model for that because it has an inherent plasticity that is really remarkable. The neurons that send taste information into the brain are also connected to taste buds. But taste buds, like your skin, are constantly turning over. The cells live for a couple of weeks and then they die, which means that the neuron that connects the taste bud to the brain is constantly remodeling and reforming its connections.

What sorts of insights have you generated?

We've illuminated to some extent the notion that connections in the nervous system are constantly remodeling. Now, there's a big gap between that level of understanding and promoting neural regeneration in a stroke victim, for example. But there's something about taste and olfaction, where the cells inherently have a lot of plasticity, and if we can understand how they accomplish that we could in theory promote plasticity in other systems. Remarkably, the olfactory system is the only part of the nervous system where new neurons are actually generated in humans even in adulthood.

You went from New York to Connecticut where you did a post-doctoral fellowship with the famous Neuro- Anatomist, D. Kent Morest, MD. You then went to Ohio State University, before ending up at UCSD. How did you wind up in San Diego?

I was recruited here by Nick Halasz who was the founding member of the Anatomy Division within the Department of Surgery. He established the clinical anatomy course of study at UCSD.

Is it the norm to have an anatomy division within a clinical department?

No, it's pretty unusual. In the 1960s and 70s, anatomy tended to be a department unto itself. UCSD started its medical school in 1968, and embarked on a really novel approach to anatomy by locating it in a clinical department. That was a concept that the school was founded on.

What are the pros and cons of placing anatomy in a clinical department?

The pros are that some of the teaching is provided by practitioners, generally in the surgical disciplines. So, when we're teaching about the heart and chest, we have a cardiothoracic surgeon present. When we're teaching about the limbs, we have orthopedic doctors help us teach. We expose the students to potential residency opportunities.

And the whole course of anatomy is geared towards a practical and clinical approach. Anybody who has seen that huge textbook, Gray's Anatomy, which is thousands of pages, realizes that there is a lot of anatomy one could teach, but we've had to make choices about what is the most important anatomy for every graduate physician to know.

You mean Gray's Anatomy a real book? I thought it was just a show. (Just kidding.)

You mean Gray's Anatomy a real book? I thought it was just a show. (Just kidding.)

It was first published by Henry Gray, an English medical student, in the late 1800s, and it's been republished and republished ever since.

What are some of the cons of placing anatomy in a clinical department?

It's a struggle for the anatomy professors to interact with clinicians. We overlap in teaching, but we anatomists don't scrub with the surgeons, so the challenge is to maintain connections. But the upsides far outweigh the downsides.

Out of the 130 or so medical students, plus 60 pharmacy doctoral students, you have a year, how many students go on to surgery?

On average, 10 or maybe as many as 15 go into a general surgery residency.

So, it's a small percentage. I imagine that surgery is one of the harder pursuits?

It depends whom you ask. Surgery is one of the more demanding disciplines. The way the students put it, it is difficult in terms of quality of life, because you generally work longer and more variable hours, and the training is pretty rigorous. Students nowadays are very savvy; they compare notes on the Internet, and they tend to look at lifestyle, income, what part of the country they want to work in.

What's special about the UCSD Anatomy program?

One of the things that's special is that our course of study is dissection-based. It is based on systematically dissecting the human body.

That's not true for most programs?

Well it turns out that that way of teaching is extremely expensive and challenging because you have to run a program that accepts and treats—appropriately, carefully, and with dignity—the remains of individuals who donate their bodies. We have one of the best programs in the country bar none. We've been very careful about how we run it and all of the donations are put to extremely good use, training medical students and doctors, and to advance research.

When you say it's expensive—how expensive?

Extremely expensive. Many schools, to circumvent that expense, use models for training students, or they will procure cadavers and keep them year after year—have one student dissect them and have other students merely look at the prosection. But we believe that the best way to learn anatomy is for students to interact with anatomical material with their hands and their eyes and their brain and develop a muscle memory.

It's also—let's be honest—a little creepy.

Anatomy has always been controversial. There were times in recorded history when taking apart a human body, even for education, was considered sacrilegious. There was a papal ban on dissection at one point. Throughout the ages, people are inherently curious about what lies inside their bodies, but it always raises issues of: is this an appropriate thing to do with a human body? Are we respecting the dignity of a human being to put them on display?

Informed consent, respecting patient autonomy, are critical for building our system and any successful, ethical systems. At UCSD, wen ensure that the donated bodies are properly respected. Every year we have a memorial service for the families of donors, and all of the bodies eventually get cremated and buried at sea, miles out from Scripps Pier.

In Anatomy in a Modern Medical Curriculum , BW Turney writes: "… in recent years, human anatomy has been slowly squeezed from the medical curriculum. For nearly 30 years, there has been discussion of the decline in undergraduate knowledge of anatomy amongst the surgical community."

Is anatomy losing its relevance?

No. You can't be a doctor if you don't know the parts of the body. But what they're getting at is the cost benefit. Part of the squeeze that anatomy has felt relates to its expense and the time it takes, and there is a lot of competition for time in the medical school curriculum. There's pressure in medical schools that adds up to: can our students learn anatomy faster and cheaper than in the past?

Can anatomy be taught cheaper and faster?

Yeah, you can teach anatomy faster and cheaper, but not as well. In their medical training, many of the senior physicians in our own department took a course of anatomy that was the better part of a year in length. But learning time for anatomy has been reduced over the years. At UCSD, we have a slightly greater than average amount of time—it's about 130 hours a year. But it was 170 hours until the curriculum reform ten years ago.

Is technology supplanting "old fashioned" anatomy?

It's certainly true that every year computerized programs for learning anatomy get more and more sophisticated. And there are some good ones—in fact we are using the best this coming year: 3-D4Med . It's a digital atlas that students can refer to when they are dissecting. These programs allow you to look at an area, and take the skin away and look just at the muscles, and take the muscles away and look at the bone. You can dissect virtually using a computer program, but you still don't have the muscle memory. You're not interacting with tissue and you're not dealing with a real human being and all the ethical and moral lessons that you obtain from working with a body.

What's ahead for the Anatomy Division?

What's ahead is dealing with the question of who is going to teach anatomy? I think the future is that anatomy teaching will be led by surgeons. The alternative is that the Department of Surgery would no longer become responsible for teaching anatomy, in which case the medical school administration would have to figure out how to do it.

If you weren't an anatomist, what would you be?

If you weren't an anatomist, what would you be?

An artist.

How come?

Artistic expression, to me, is transcendentally creative and fulfilling.

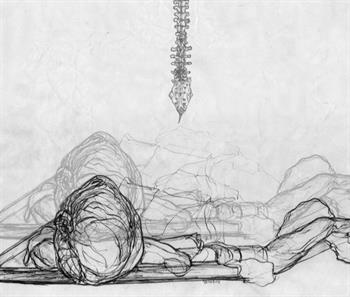

Check out the work of Joyce Cutler Shaw, UC San Diego School of Medicine's Artist-in-Residence. In The Anatomy Lesson ,she approaches the body as a matrix of the human condition and the study of its territory as a geography.