How Should Surgeons Get Paid?

September 14, 2018 | Lindsay Morgan

Health financing strategies that incorporate incentives for good performance are being introduced in many U.S. healthcare systems, with improvements in quality, efficiency, and outcomes as central goals. As part of that trend, UC San Diego has begun to test a modification to its approach to paying physicians, one it hopes will improve the quality of care, focus attention on data and costs, and ultimately improve health. This article reviews the new approach, explores provider perceptions; and discusses opportunities for the future.

For decades, health systems and physician practice groups in the United States have tended to employ variations on one of two basic models for compensating physicians: a salary paid largely irrespective of clinical volumes, or a modest base salary plus a significant percentage of fee-for-service (FFS) revenues associated with each clinical encounter. Both models carry the risk of perverse incentives. The salary model may incentivize low productivity, while the FFS approach can lead doctors to over-provide procedures.

While changing employment trends have shifted more surgeons into hospital salaried positions in recent years, the compensation of most surgeons remains tightly associated with the number and types of procedures they provide. But momentum is growing to apply new financing models that provide stronger incentives for quality, efficiency, and patient satisfaction. Referred to as pay for performance and value-based purchasing, these schemes aim to improve the quality of care, focus attention on data and cost, motivate the workforce, and ultimately improve health.

Surgeons and their counterparts are not solely motivated by money, of course. Physicians work within complex ecosystems, and there are many factors that drive behavior—social norms among physicians, a desire for peer recognition, intrinsic motivation to care for patients, and a desire to avoid bad things like getting sued or reprimanded for not following guidelines (Levine and Eichler 2009).

But money is a powerful motivator and numerous pay for performance programs have been introduced and evaluated worldwide over the last several decades (Clemens and Gottlieb 2014; Chaix-Couturier et al 2000; Doran et al 2017; Eijkenaar et al 2013; Levine and Eichler 2009).

In 2004, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) began the Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration, its first major experment with value-based payment. The enactment of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 created new value-based payment programs—such as the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing program, among others—for virtually all the services covered by Medicare (Doran 2017).

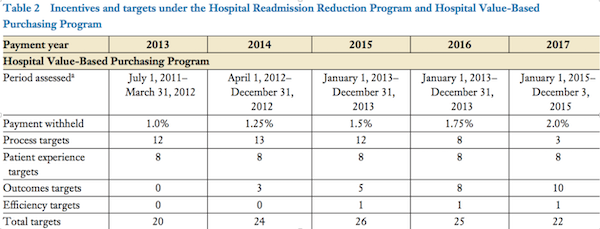

Beginning in 2013, CMS began to withhold a portion of payment based on hospital performance on a range of quality indicators. Drawing on Donebedian 1966, the indicators include structural, process and outcome measures of quality (Table 2). The percent withheld—and paid back to hospitals based on performance—has grown over time, from 1 percent the first year, to 2 percent today. The indicators have similarly evolved: in the first year, clinical process of care indicators represented the largest chunk, but emphasis on outcomes and efficiency is growing.

(Doran 2017)

The ACA transformed CMS from a passive payer to active purchaser of higher quality, efficient health care, and following suit, many insurance companies are changing the way they reimburse doctors—increasingly moving away from fee-for-service models and towards incentivizing quality and patient satisfaction. UnitedHealth Group, for example, reported earlier this year that nearly 60% of the insurer’s $130 billion in annual medical spending is value-based models.

At UC San Diego, the new payment rules spurred the hospital to introduce campaigns to improve quality and promote best practices, such as appropriate use of antibiotics and blood clot prevention medication prior to surgery. Performance on those process of care measures promptly improved.

“It immediately changed what hospitals did, including ours.” says Sonia Ramamoorthy, Chief of the Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery and Vice Chair for Quality. “It changed things in a way that just making suggestions to providers in health systems had minimal impact. It’s one thing to say: please pay attention to your surgical outcomes. Well, yeah, I always pay attention to my surgical outcomes. But if you tell me that you’re going to withhold a percentage of our health system’s payment for these specific measures, then I’m gonna pay a lot of attention to those metrics.”

Despite the shift in financing at the hospital level, surgeons at UC San Diego continued to be paid primarily on the basis of clinical productivity, or work RVUs—relative value units—a model similar to fee for service, wherein each service provided—an appendectomy, for example—is assigned a dollar amount, and physicians are paid based on how many procedures they do / how many patients they see, over the course of a year. The RVU-based compensation models were introduced to encourage improved patient access and increased clinical productivity and to assign a value to physician services, be it an intervention such as surgery or a clinic visit. Following its introduction, volume promptly rose, such that today, nearly every surgeon in the Department is above national median productivity.

Today, as the hospital is increasingly held financially accountable for “value,” interest has grown within the administration to better align accountability between the hospital and physicians—and to prepare for impending national changes in how providers are paid (Box).

Box. Changes to U.S. Physician Payment Under CMS.

In April 2015, the Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (MACRA) effectively repealed the sustainable growth rate formula that measures increases to provider payments against changes in GDP. Beginning in 2019, all clinicians who bill Medicare (e.g., physicians and nurse practitioners) must participate in either the alternative payment model (APM) or the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS), both of which are value-based payment models. MACRA will eventually form the largest value-based purchasing program in the United States.

(Credit: Doran 2017)

Pay for Quality at UC San Diego

For fiscal year 2019, hospital departments at UC San Diego were tasked with introducing compensation plans that require at least 1 percent of physician pay to be tied to performance on quality indicators. Each department was asked to choose three quality indicators per specialty or division, and propose targets to be met by the end of the fiscal year. These were reviewed and approved by each department compensation committee and by the hospital compensation committee.

Table 1 Department of Surgery Quality Indicators and Targets

| Division | Quality Metrics | Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Breast Surgery |

|

|

| Colorectal Surgery |

|

|

| MIS/Bariatrics |

|

|

| Otolaryngology/Head & Neck Surgery |

|

|

|

Plastic Surgery |

|

|

|

Surgical Oncology |

|

|

|

Transplant |

|

|

|

Trauma/Burn/ |

|

|

|

Vascular Surgery |

|

|

Department of Surgery indicators are a mix of process and outcome measures, some of which have targets to achieve, while others are all or nothing. All divisions are being held accountable for new patient visits within 7 days, which is a health system goal; the remaining two indicators per division are specialty specific.

Although performance is measured at the level of the division, the incentive targets each individual surgeon. One percent of their income is withheld throughout the year, and then “earned back” according to their division’s performance on quality. To qualify for receipt of the full 1 percent withheld, a physicians’ divisions must meet targets for all three indicators. If they achieve two of three, they receive .66 back. If they achieve one of three, they receive .33 back.

Discussion—Perceptions Among Surgical Faculty

What do surgeons think about the new payment model? Interviews with Department of Surgery faculty revealed areas of striking consensus, and areas where views diverge.

Most stakeholders agree that moving away from the fee-for-service model and toward a model that rewards other dimensions of care is appropriate and welcome, and many appreciate that responsibility for choosing quality metrics and targets was left to their discretion—versus being imposed from above.

“I think it’s a good start,” says Kristin Mekeel, Interim Chief of the Division of Hepatobiliary and Transplant Surgery. “Healthcare is moving towards value-based systems and this is a great chance for us at UC San Diego to get our feet wet and figure out what is important to us.”

Stakeholders also roundly acknowledged the risk of perverse incentives in fee-for-service models—unnecessary care, and a drive to be ever busier, behaviors that can result in burnout and complications.

Despite an acknowledgement that this is a move in the right direction, holding physicians accountable through external incentives is a cultural shift in a sector where strong intrinsic motivation is generally assumed. Suggesting that there might be other motivators is sometimes taken as an insult.

“Getting physicians to change behavior is hard,” says Mekeel. “It can be difficult to gain traction for quality programs because physicians see them as punitive, and a lot of extra work, when surgeons already have so much on their plates.”

“Getting physicians to change behavior is hard,” says Mekeel. “It can be difficult to gain traction for quality programs because physicians see them as punitive, and a lot of extra work, when surgeons already have so much on their plates.”

But some think the shift may be needed anyway. Ramamoorthy notes: “Quality has always been an aspect of surgical care and medical care, and surgical morbidity and mortality conference is a testament to that. We’ve just never been held accountable for it by anyone else. It’s always been a personal accountability to your patient. With the new approach, they’re trying to get us to be more conscious of how we practice, the cost of care, and the efficiency of care. There can be a huge variation in costs between hospitals, even between providers. And truthfully, as a physician, I wasn’t always aware of the costs of the products I was using. I just used what I thought I needed to use, without giving much thought to whether one was more cost effective than the other.”

But some think the shift may be needed anyway. Ramamoorthy notes: “Quality has always been an aspect of surgical care and medical care, and surgical morbidity and mortality conference is a testament to that. We’ve just never been held accountable for it by anyone else. It’s always been a personal accountability to your patient. With the new approach, they’re trying to get us to be more conscious of how we practice, the cost of care, and the efficiency of care. There can be a huge variation in costs between hospitals, even between providers. And truthfully, as a physician, I wasn’t always aware of the costs of the products I was using. I just used what I thought I needed to use, without giving much thought to whether one was more cost effective than the other.”

The biggest area of concern among faculty is the incentive model itself and a perception that it exacerbates rather than ameliorates existing dysfunctional incentives.

Designing effective financing interventions requires clear understanding of the pre-existing incentive environment—what are the different sources of physician remuneration, and what are the non-financial factors that are either demotivating or motivating the workforce?

Introducing a salary withhold—even a small one—into an environment characterized by, for example, concerns about equity in compensation, or a lack of physician voice in leadership, or frustrations that academic and research productivity are not linked to monetary “rewards,” could have the opposite of the intended effect—and actually demotivate rather than motivate.

Many suggested that a bonus may be more appropriate—and motivating—but concerns have been raised about the sustainability of additional funding for good performance.

“I think the honest answer is, if you have a carrot approach you have to find the money somewhere,” said one Department administration official. “Now I think that’s ok, because if you provide better quality, you will have excess revenue.”

Another question is how to best incentivize team effort, since quality is a “team sport.” It is one thing to hold a physician accountable—but how can health systems best incentivize, motivate, and hold accountable nurses, techs, non-physician staff and administrators who are also responsible for creating an environment that delivers excellent patient care?

Opportunities Ahead

As with the introduction of any new financing approach, there are many concerns, but there is also consensus that moving away from the pure RVU system and towards systems that reward quality and outcomes—models that other health systems such as Geisinger Health System have enthusiastically introduced—is the right thing to do. Indeed, some divisions in the Department of Surgery have already moved away from an individual RVU payment model towards one that provides salaries for the clinical component of faculty portfolios, plus incentives for quality and academics.

Says Mekeel: “Switching from a productivity based model to being quality based is the right direction. But how to make it meaningful—to ensure it really is improving our practice and motivating our physicians—is something the whole Department is going to have to evolve into over time.”

Making it meaningful will require more conversation about what is the best incentive approach, and which measures of quality and outcomes are most appropriate. It will also mean anticipating and mitigating risk, so that the perverse incentives of one financing model are not simply replaced with the perverse incentives of another. For example, although outcomes—better health, less time lost to sickness, lower mortality—are the ultimately goals of health care, paying for reduced mortality may encourage providers to turn away the sickest patients to avoid penalties.

For this reason, some argue that providers should be paid, not for outcomes, but for following evidence-based practices: “You can’t blame a medical team or a surgeon for an outcome if the evidence-based practices were followed,” says one Department of Surgery representative. “A lot of things happen in between. That’s why I wish here that we would focus more on process and standardizing evidence-based practices. Not only is this better for patients, because physicians are delivering care in a way that is known to maximize health, but cost also decreases.”

Ramamoorthy agrees: “If a patient comes in with morbid obesity, uncontrolled diabetes or a history of smoking—all factors known to increase risk of complications—a physician cannot refuse to care for the patient or ask for a 'new patient' with better health. Measuring outcomes is necessary to improve care but it also has to be a reasonable, risk-adjusted process that incorporates patient-related factors that adversely impact care.”

Because pay for performance schemes rely heavily on data, strengthening health information management systems is also important. If data is unreliable or its acquisition not transparent, pay for performance schemes run the risk of being perceived as unfair, if physicians distrust the data that is being used to judge their performance.

UC San Diego has made significant strides over the last several years in health information management and efforts are underway to strengthen physician access to the data they need to improve their practice.

Fundamentally, the opportunity is ripe for tackling other elements of the environment that motivate and demotivate physicians—for example, support for academic and research endeavors—and for increasing transparency about the way physicians are paid.

As one surgical faculty member put it: “Surgeons are humans and with that comes human nature. We respond to incentives just like everybody, whether we acknowledge it or not. The more we own up to the fact that we are human, the better off we will be and our patients will be.”